|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Page: 3 of 3

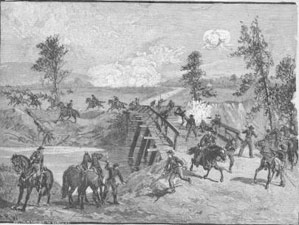

Report of Lieut. Col. Porter C. Olson, Thirty-sixth Illinois Infantry. HDQRS. THIRTY-SIXTH REGIMENT ILLINOIS VOLS., Chattanooga, Tenn., November 28, 1863. At 1 o'clock on the morning of the 26th November, by order of Colonel Miller, the Thirty-sixth Illinois moved in pursuit of the enemy with the rest of the brigade upon the road toward Chickamauga Station. On the afternoon of the same day we returned with the brigade to Chattanooga. Throughout the entire engagement

the officers and

men under my command behaved with the greatest gallantry and coolness.

Though

they have conducted themselves bravely and nobly on former fields, it

seems to

me that on this occasion the regiment has added a new and brighter

luster to

their already good name and well-earned laurels. I do not know that

they

exceeded the men of other regiments in this action, for all seemed to

vie with

one another in deeds of daring; but this

I do

believe, that their conduct for bravery and almost superhuman exertion

has

never been surpassed in any army. Their names will be held in

remembrance by a

grateful country. Of the conduct of the enlisted men the facts stated in this report form a more brilliant compliment than any other that could be given. I must, however, mention the name of the flag bearer, Private William R. Fall, of Company C, for bravery. He can have no superior; he was among the first to reach the summit and wave the Stars and Stripes in the face of the enemy. It is

not for me to

comment upon the conduct of my superiors, but I desire to state that

the conduct

of Colonel Miller, of this regiment, was especially conspicuous

for

gallantry; he rode along the line exposing himself with the most

perfect

coolness, directing, encouraging, and urging forward the exhausted men

of

whatever regiment he found. I make this statement as an acknowledgment

of his

assistance, not that anything I could say would add to his high

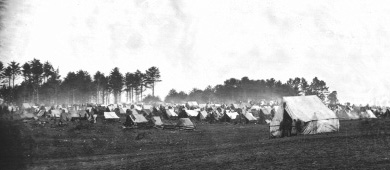

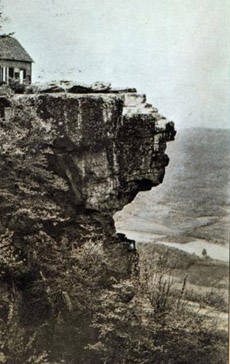

reputation. To this report I append a list of casualties. Your obedient servant, PORTER C. OLSON, The following excerpts are from the book A former Indian trading village once known as Ross Landing, Chattanooga had fallen on evil days by 1863. The town of Chattanooga "must have been a nice place in times of peace," observed an Illinois officer, who was thoroughly amazed at the large network of railroad switches and side tracks at the southern end of town. Huge depots, warehouses, and two foundries dominated the scene, reflecting Chattanooga's status as a burgeoning railroad and industrial site before the Civil War. It was the railroads that had changed the town's destiny. Due to their influence, Chattanooga had become popularly known as "the gateway to the South." Wartime had brought a prolonged season of despair, noted the Reverend Dr. Thomas H. McCallie, the sole remaining local civilian minister following Chattanooga's September 9, 1863 occupation by the Federal army. "All without was winter. It was winter in the city and winter in the state. War had devastated everything," he sadly noted. His Presbyterian church on Market Street had been converted on September 21, 1863, into a hospital. Pews were torn out, cots installed, and hundreds of wounded Federals from the Chickamauga battlefield covered the floor. Confusion and chaos reigned in the city. Civil authority was suspended; stores and markets were closed. The town became white with a sea of tents, including a few sutler's shelters, which contained but little merchandise. There was barely enough food--no milk, no butter, no cheese, and hardly any fruit for the town's remaining populace. For sustenance, the citizens relied on bacon, bread, what salted meat and pickles they had preserved in barrels from earlier times, and a little coffee. Most families remained indoors. As the siege of Chattanooga progressed, an insidious despair had settled over the community." With the approach of the Confederate army on September 22, various outlying residences had been burned due to military expediency. The Federal commanders wanted no place of refuge for enemy sharpshooters between the lines, or a restricted view of Rebel positions. As a result, the blackened chimneys of once-prosperous residences stood stark against a sky hazy with smoke, noted a Federal lieutenant on the morning after the burning. Everywhere there was the relentless turmoil of war...So many stately trees were downed that by 1865 only fifty-one shade trees remained standing in the city. Then, with the advent of cold winter weather, so desperate for fuel became the multitude of soldiers that servants' quarters, smokehouses, doors from residences, and even household furniture were taken." Chattanooga's wretched facade had become all-pervasive. The town was only a dingy military camp, with the rights of citizens humbled, regardless of wealth or social standing. Many remaining townspeople were ordered to leave the city. Go north or go south, they were told, but leave Chattanooga. For good reason, many had already left in despair. A Yankee enlisted man was amazed to discover in one house the families only calf and a disassembled board fence piled inside the parlor to protect them from pillage. "There is not a pig running loose inside our lines," he joked. Chattanooga was devoid of commercial activity, especially since most inhabitants were required to stay in their homes. A few managed to work for the Federal army, being paid in food, which was "the way the Rebels get their rights," decreed an unsympathetic soldier. Shrugging off all the manifest misery and squalor, Pvt. Bliss Morse of the 105th Ohio mused, "I supposed it [Chattanooga] looks no worse than many other Southern towns our army has been in." All of this agony and ordeal had been presaged, some said, by the meteor episode of 1860. Amid the presidential campaign of that summer and fall, various political speakers, including Stephen A. Douglas, had visited Chattanooga to address the citizens. During one of the frequent political speeches of that year, a meteor had streaked across the sky, breaking into two parts. Word soon spread that it was of ominous portent; the country would split into two halves. Chattanooga thereafter had suffered much. And now there was only more misery in the offing. ...Many of Rosecran's men seemed sanguine and hopeful despite the recent debacle at Chickamauga. "Our army is all together again and in good order. Let them come on and God grant us the victory," wrote twenty-one year old Chesley Mosman, a lieutenant in the 59th Illinois Infantry Regiment. The random fighting along the front lines soon degenerated into scattered sniper firing, and aside from patrols or a few probing reconnaissances by small units, there were only occasional blasts of cannon fire to shatter the gathering quiet. Once the initial concerns about a Rebel attack had abated, the men began to regard their circumstances and the results of the past few weeks in a different light. "We do not feel exactly whipped," announced a Federal soldier to his family on October 2. "neither do [we] feel we gained nothing. For we should have had a fight anyway to get this place. We have it to their sorrow. It is so much gained. I hope we can hold it. Let the reinforcements come." ...The attitude of well being was soon revealed as so much false euphoria following a narrow escape from disaster. There were so many difficulties burdening the Federal army at Chattanooga that concern about a direct enemy attack was among the least worrisome. In fact, as the days and weeks progressed, it was the soul of the Federal army that was in doubt. The men and their leaders were to be tested psychologically to the fullest extreme. Instead of the prospect of facing an attack from behind well-prepared entrenchments, it was soon manifest that the bloodied and beaten Army of the Cumberland must attack the surrounding heights in order to survive. ...By mutual agreement, during the several days' journey of the ambulance train, the pickets on both sides were ordered not to fire at one another. The importance of this truce as a subtle opportunity for the soldiers to chat and interact with their opponents was soon realized by troops in both armies. All along the lines, there were frank and practical discussions among both armies' rank and file. On the twenty-seventh, a Federal officer wrote how he was able to take a bath in Chattanooga Creek, within plain sight of a Rebel picket. "As he was so amiable, I went out to talk to him," wrote Lt. Chesley Mosman in his journal. "He didn't feel elated over the battle and says, "we didn't whip you fellows much." "One of Longstreet's men, the enemy picket acknowledged that they had found a big difference between eastern and western Yankees. Matters soon went beyond sociability. Some of the troops agreed that as an extension of the existing ambulance truce there would be no further shooting along the picket lines unless the other side made a general advance. This arrangement spread along the front lines until a general "understanding" prevailed. A Regular officer, a lieutenant in the 18th US Infantry, described with amazement in a letter home the remarkable change that had occurred. "When we first took our position here after the battle [of Chickamauga] the pickets would have to lay down and keep under cover...for if he stuck his head up...a bullet would be sent after him." Since the lines were in places only about one hundred yards apart, under the new no-shooting arrangement, "They exchange papers, and even go down between the lines and have a social talk," he observed. To Lieutenant Mosman, the informal truce was appropriate. It "seems wrong to murder a fellow for not doing anything offensive," he acknowledged. "Instead of shooting at them we talk to them and ask them to come over to our side of the creek for a chat and a game of euchre." With the idle pickets in full view of one another on the evening of September 29, the returning ambulance train of about two hundred wagons loaded with 1,742 Federal wounded rumbled through the lines to the tune of bands playing at Fort Negley. Chesley Mosman found pickets from the 6th South Carolina Infantry in his front. To his surprise, they were " a fine, handsome, stout lot of fellows, better dressed than we are, their uniforms being apparently new." With soldiers from both armies filling their canteens from the same creek, a lively trade in tobacco for coffee and the exchange of newspapers was in progress. When Lieutenant Mosman found several privates from the 74th Illinois playing cards with the Johnnies, he recorded in his journal: "Ain't that a queer kind of war?" Another soldier, a member of the 85th Illinois, discussed the general situation with a nearby Confederate picket. "Say boys," said the Rebel, "this is all a damned piece of foolishness. Let's all quit and go home." The Yank benevolently agreed in principal, admitting that there was "some truth to that." As a Confederate captain noted, "If the terms of peace had been left to the men who faced each other in battle day after day, they would have stopped the war at once on terms acceptable to both sides." A particularly thoughtful Federal soldier acknowledged in a letter home: "One of the boys in my company was out and talked with them [Rebels], he traded his pipe and pocket knife to them for tobacco. It is strange that they will talk to one another one moment and maybe the next they may be in deadly conflict with each other. As for my part, I begin to think it is time for this thing [war] to stop. We have seen enough of men butchered." There was no truce among artillerists. The guns continued to roar during the ever-shortening Autumn days, until an hour-long sporadic cannonading was considered commonplace. It was a constant reminder of the "realities of our circumstances," remembered a Federal soldier. Beginning on September 25, when heavy cannon began firing from Lookout Mountain, the long-range bombardment of Chattanooga had been a regular occurrence. Although at first a source of dread, lumbering shells were randomly dispersed and inaccurate. For example, the October 5 bombardment had caused only a single injury, it was learned: that of a private in the Fourteenth Corps who was struck in the leg. After estimating that the Rebel guns were about two miles distant, one rather indifferent Ohio infantryman remarked in a letter home: "It would not seem very pleasant to any to any of you, I dare say, to have your sleep broken by cannonading [at] any hour during the night. Yet we have this music every night, and snooze away--perhaps asking the question: '[Do you] think that was our gun or the Rebs?" To the battle-hardened Federal veterans who had faced many devastating close-range artillery blasts, the enemy's ineffective long-range practice, even if from commanding heights, was soon regarded as a minor annoyance." "[The Rebels] have wasted a great deal of ammunition," wrote Capt. John S.H. Doty of the 104th Illinois Infantry, "for they have fired from here, and I don't think they kill a man once in a month." Doty dismissed the danger, saying, "It seems that their shelling from that mountain does not amount to much, or has not so far." Another unimpressed officer agreed, scoffing that the "shells don't do [us] much harm." To a youthful Federal lieutenant, the Confederate cannon on Lookout Mountain were so notoriously inaccurate that he joked in a letter home about the scene witnessed on October 10. The men were all in line to answer roll call about noon when a shell from Lookout Mountain struck in the center of the 18th US Infantry's camp. "It was a percussion shell, and struck on a rock and exploded beautifully" near Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau, noted the lieutenant, "The next shell passed ...over General Rousseau's house and struck right in front of the door of General King's house, [only[ about four feet behind a man who was carrying water. As the shell struck the ground he fell water and all, [then] kicked with his legs to see if he was still alive." The man hastily got up and walked away to the laughter of all." When several shells fell in the camp of the 2nd Minnesota Infantry, a sergeant saw Gen. George H. Thomas standing on the wall of a nearby fort, looking nonchalantly at the scene. A few men were seen running as several shells passed overhead, causing the men of the 59th Illinois Infantry to have a good laugh. Instead of the supposed safety in scurrying away at the sound of an incoming shell, one soldier mused, "Motion is as likely to carry one into as [well] as out of its way." One wildly bounding solid shot, striking the ground in front of a campfire, knocked a frying pan out of a soldier's hand, then careened into a stump behind which another man was sitting. "The shell was hardly cool when the boys had it on exhibition, passing it from hand to hand," wrote an amazed onlooker. Fortunately for the soldiers' peace of mind, there were other, far more agreeable sounds emanating from around Chattanooga during the siege. One Federal private was almost homesick from listening to the sound of band music wafting across the valley on a balmy evening. Both armies contained various regimental bands, and the strains of favorite songs such as "Yankee Doodle", "The Battle Cry of Freedom," and "The Bonnie Blue Flag" entertained soldiers on both sides.

|

|||||||||

Capt. Silas Miller On July, 1864 in Nashville, Tennessee, Colonel Silas Miller died from wounds received at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia |

Lt. Charles Trumbull |

Gettysburg reenactment 1998

ILLINOIS: LAND OF LINCOLN

THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS

"Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth

on this continent a new nation: conceived in liberty, and dedicated to

the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war...testing whether that nation,

or any nation so conceived and so dedicated...can long endure. We are

met on a great battlefield of that war.

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting

place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.

It is all together fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a

larger sense, we cannot dedicate...we cannot consecrate...we cannot

hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here

have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The

world will little note nor long remember, what we say here, but it can

never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be

here dedicated to the unfinished work which they who fought here have

thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining

before us...that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to

that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion...that

we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in

vain...that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of

freedom...and that this government of the people...by the people...for

the people...shall not perish from the earth."

President Abraham Lincoln

"It seems strange to me how much

there is in the Bible about dreams."

Abe Linoln to his wife Mary Todd Lincoln

MR. LINCOLN'S DREAM

"About ten days ago, I retired

very late. I had been up

waiting for important dispatches from the front. I could not have been

long in bed when I fell into a slumber, for I was weary. I soon began

to dream. There seemed to be a death-like stillness about me. Then I

heard subdued sobs, as if a number of people were weeping. I thought I

left my bed and wandered downstairs. There the silence was broken by

the same pitiful sobbing, but the mourners were invisible. I went from

room to room; no living person was in sight, but the same mournful

sounds of distress met me as I passed along. I saw light in all the

rooms; every object was familiar to me; but where were all the people

who were grieving as if their hearts would break? I was puzzled and

alarmed. What could be the meaning of all this? Determined to find the

cause of a state of things so mysterious and so shocking, I kept on

until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a

sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a

corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers

who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, gazing

mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping

pitifully. 'Who is dead in the White House?' I demanded of one of the

soldiers, 'The President,' was his answer; 'he was killed by an

assassin.' Then came a loud burst of grief from the crowd, which woke

me from my dream. I slept no more that night; and although it was only

a dream, I have been strangely annoyed by it ever since."

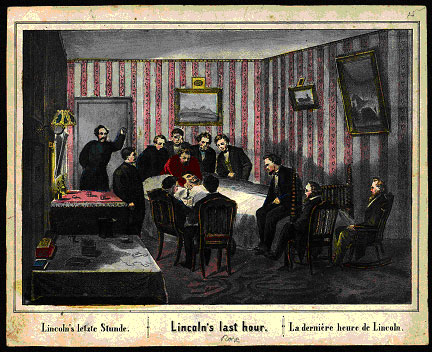

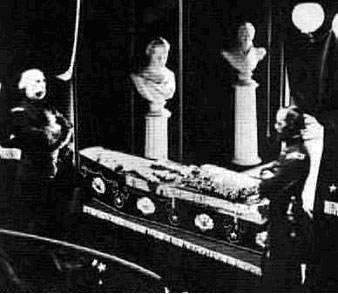

DEATHBED SCENE OF THE MURDERED PRESIDENT

As soon as the discovery was made that the President was shot, the surgeon-general and other physicians were immediately summoned and their skill exhausted in efforts to restore him to consciousness. An examination of his wounds, however, showed that no hopes could be given that his life would be spared.

Preparations were at once made to remove him, and he was conveyed to a house immediately opposite, occupied by Mr. Peterson, a respectable citizen of that locality. He was placed upon the bed, the only evidence of life being an occasional nervous twitching of the hand and heavy breathing. He was entirely unconscious, as he had been ever since the assassination. At about half past eleven the motion of the muscles of his face indicated as if he were trying to speak, but doubtless it was merely muscular. His eyes protruded from their sockets and were suffused with blood. In other respects his countenance was unchanged.

At his bedside were the Secretary of War, Secretary of the Navy, Secretary of the Interior, Postmaster General and Attorney General; Senator Sumner, General Todd, cousin to Mrs. Lincoln; Major Hay, M. B. Field, General Halleck, Major-General Meigs, Rev. Dr. Gurley, Drs. Abbot, Stone, Hatch, Neal, Hall, and Lieberman, and a few others. All were bathed in tears; and Secretary Stanton, when informed by Surgeon Gen. Barnes, that the President could not live until morning, exclaimed, “Oh , no, General; no—no;” and with an impulse, natural as it was unaffected, immediately sat down on a chair near his bedside, and wept like a child. Senator Sumner was seated on the right of the President, near the head, holding the right hand of the President in his own. He was sobbing like a woman, with his head bowed down almost on the pillow of the bed on which his illustrious friend was dying. In an adjoining room were Mrs. Lincoln, and her son, Capt. Rob’t Lincoln; Miss Harris, who was with Mrs. Lincoln at the time of the assassination, and several others.

Mrs. Lincoln was under great

excitement and agony, wringing

her hands and exclaiming, “Why did he not shoot me instead of my

husband? I have tried to be so careful of him, fearing something would

happen, and his life seemed to be more precious now than ever. I must

go with him,” and other expressions of like character. She was

constantly going back and forth to the bedside of the President,

exclaiming in great agony, “How can it be so! The scene was

heart-rending. Captain Robert Lincoln bore himself with great firmness,

and constantly endeavored to assuage the grief of his mother by telling

her to put her trust in God and all would be well. Occasionally,

however, being entirely overcome, he would retire by himself and give

vent to most piteous lamentations. Then, recovering himself, he would

return to his mother, and, with remarkable self-possession, try to

cheer her broken spirits and lighten her load of sorrow.

"Bring Tad. He will

talk to Tad. He loves him so." - Mary Todd Lincoln

At four o’clock the symptoms of restlessness returned, and at six the premonitions of dissolution set in. His face which had been quite pale, began to assume a waxen transparency, the jaw slowly fell, and the teeth became exposed. About a quarter of an hour before the President died, his breathing became very difficult, and in many instances seemed to have entirely ceased. He would again rally and breathe with so great difficulty as to be heard in almost every part of the house. Mrs. Lincoln took her last leave of him about twenty minutes before he expired, and was sitting in the adjoining room when it was announced to her that he was dead. When the announcement was made, she exclaimed, “Oh! Why did you not tell me that he was dying!”

The surgeons and the members of the cabinet, Senator Sumner, Captain Robert Lincoln, General Todd, Mr. Field, and Mr. Rufus Andrews, were standing at his bedside when he breathed his last. Senator Sumner, General Todd, Robert Lincoln, and Mr. Andrews, stood leaning over the headboard of the bed, watching every motion of the beating breast of the dying President. Robert Lincoln was resting himself tenderly upon the arm of Senator Sumner, the mutual embrace of the two having all the affectionateness of father and son. The surgeons were sitting upon the side and foot of the bed, holding the President’s hands, and with their watches observing the slow declension of the pulse, and watching the ebbing out of the vital spirit. Such was the solemn stillness for the space of five minutes that the ticking of the watches could be heard in the room.

At twenty-two minutes past seven o’clock, in the morning, April fifteenth, gradually and calmly, and without a sigh or a groan, all that bound the soul of Abraham Lincoln was loosened, and the eventful career of one of the most remarkable of men was closed on earth.

As he drew his last breath, the Rev. Dr. Gurley, the President’s pastor, offered a fervent prayer of supplication and sympathy. The countenance of the President was beaming with that characteristic smile which only those familiar with him in his happiest moments could appreciate; and except the blackness of his eyes, his face appeared perfectly natural. The morning was calm, and the rain was dropping gently upon the roof of the humble apartment where they laid him down to die. The body servant of the President entered the room just before he died, and as the breath left the body of Mr. Lincoln, this loving and bereaved servant manifested the most indescribable sorrow. Mrs. Lincoln remained but a short time, when she was assisted into her carriage, and with her son Robert and other friends she was driven to the house which but the evening before she left for the last time with her honored husband, who never was again to enter that home alive.

The room, into which the most exalted of mortal rulers was taken to die, was in the rear part of the dwelling, and at the end of the main hall from which rises a stairway. The dimensions of the room are about ten by fifteen feet, the walls being covered with a brownish paper, figured with a white design. Some engravings and a photograph hung upon the walls…

Everything on the bed was stained with the blood of the Chief Magistrate of the nation. A few locks of hair were removed from the President’s head for the family, previous to the remains being placed in the coffin temporarily used for removing the remains to the executive mansion.

- from The Book of Anecdotes of the Rebellion

"The death of

Lincoln was a disaster for Christendom. There was no man in the United

States great enough to wear his boots and the bankers went anew to grab

the riches. I fear that foreign bankers with their craftiness and

tortuous tricks will entirely control the exuberant riches of America

and use it to systematically corrupt modern civilization."

- Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor (1815-1898)

Play: Stand

Still Jordan

Let a child of God go home

Because his battle has been fought

And his victory has been won.

- The Uplifters

“Now he belongs to the Ages.” - Secretary Stanton

Email me: tom@wolfkiller.net

©Copyright 2001-2007 All rights reserved.

The copyright laws of the United States protect the information

available on this website.

Permission must be granted to use any text, music, or images from this

site.

Chamberlain took up

arms to

preserve the Union and to end slavery. Holding these things worth

sacrificing himself for, Chamberlain described them in almost spiritual

terms.

Chamberlain took up

arms to

preserve the Union and to end slavery. Holding these things worth

sacrificing himself for, Chamberlain described them in almost spiritual

terms.